I hate being late. Standing in the middle of a busy parking lot in Yosemite Valley, totally lost and overwhelmed by the hoards of equally confused tourists, I looked up to remind myself that it was a blessing just to be there. Unfathomably tall, stark slabs of granite walls were beginning to obscure the sun, leaving dramatic contrasts of golden light against the greying boulders. They also blocked cell phone service. I’d already gotten lost on the drive down into the valley, accidentally taking a one-way exit from the park and turning the wrong direction into a shuttle lane. I could figure out where I needed to be if I could just get my bearings straight. That would be easier to do without the anxious energy of eager tourists, parking lots filled with dirtbags and their climbing gear, or the seemingly hundreds of middle-grade children running around screaming, “Marcus kissed a lizard! Marcus kissed a lizard!!”

We were all there to experience one of the most visited, iconic National Parks on a perfectly warm late September week. The only question was: which of us were there to enjoy the park the right way, and which were there to destroy it?

I ditched the crowd and started walking to orient myself. Pedestrian paths crisscrossed over multiple lanes of traffic, thankfully moving at a snail’s pace. Roads once used for traffic had been repurposed and rerouted to accommodate expanded development in the Valley, creating awkward corners and misdirections. The post-WWII tourism encouraged most of this initial development in hopes of attracting middle-American road trippers to the newly accessible outdoors. This came at the deliberate cost of removing the remaining Native Americans who had been allowed to continue living on their ancestral land (albeit restrictively) until this midcentury boom.1 Interpreting the map felt less like exploring the vast wilderness and more like navigating an amusement park. Still, looking up in any direction, I was reminded that I’d just driven 2,300 miles across the country for a reason. In the distance, I finally saw a collection of tents, banners, and, increasingly, people in orange vests.

It was the 21st Yosemite Facelift volunteer event. Over the past two decades, tens of thousands of volunteers have removed over 1,200,000 pounds of trash and debris from Yosemite and other public land areas through this initiative. Hosted jointly by the Yosemite Climbing Association and the National Park Service, the goal is to involve the public in conservation efforts in one of the most heavily trafficked natural areas in the country. Whether participating in conservation or joining a lecture on geological history, it’s a chance to teach even the most casual visitor about what it takes to keep Yosemite healthy for generations. It’s also an opportunity to learn about the history of rock climbing in the park – a culture that has long been at odds with its host institution.

As wholesome midcentury families flooded into new, pristine campgrounds, soon, too, did the dirtbags. Beckoned by Dharma Bums and growing legends, beatniks and hippies began communing with the “vertical wilderness” of Yosemite. Some had come to connect with the earth and live free among the boulders; some had come to party and trash the meadows. Clashes with park rangers led to increasing restrictions and questions over who has the right to determine how this land can and cannot be interacted with. Though the tension between open access and reducing overcrowding still remains, projects like Facelift work to bridge the gap between the park and the public.

After I’d walked off the crowds and disorientation, I headed over to meet the team who invited me. I navigated through the Lower Pines Campground until I saw a group of a dozen people, all wearing The Landmark Project sweatshirts and hats. They’d assembled a group of their team members, plus a few content creators, photographers, and writers, to pitch in for a few days; I happily agreed to join in exchange for gas money. Dedicated to their own environmental mission of donating 10% of their sales to conservation partners, The Landmark Project returns to these projects again and again to put their words and financial pledges into tangible action. They recognized my Leave No Trace hat and waved me over to the group gathered around the campfire.

“We flew into Vegas from Greenville a few days ago and have been camping in the Sierras,” Jeremy, one of the brand’s team members, told me in a comforting southern accent. “It was way colder than we expected.”

I commiserated, “I know! I’ve been keeping the heat on in the van. I’ve been camping since I drove over from Atlanta last weekend.”

He blinked. “You drove all the way here? Why?” Our homes were barely a three-hour drive up I-85 apart, so I understood his confusion.

But I didn’t have a great answer for him. “I dunno… guess I just prefer to experience the park this way, in my own van. Even if it means driving for three days, it’s comfortable and gives me flexibility.” We continued sharing notes on our recent camping and were joined by the brand’s founder, Matt Moreau.

Matt extended his arm and welcomed me to camp. His charming smile and confident handshake were emblematic of a startup founder, minus the arrogance of the tech industry. Always a little “on,” Matt seemed ready to rally the tired team, or ask an unexpectedly profound question, or pitch a bystander on a free t-shirt. Matt offered me a drink and a stick to roast hot dogs before we gathered together to plan out the next few days.

“We all have a story to tell here,” he encouraged us. “Even if it’s your first time in the park, we all have a part to play in keeping this place healthy for generations to come.” The crackling fire released billows of smoke into the thick cedar tree canopy above our circle. I sipped a Modelo as each group member explained their excitement for the work we’d be doing together, starting bright and early. “No one has to come for sunrise,” Matt explained, “but if you’ve never been, I highly encourage it.” I was two drinks in and eager to agree.

Back at Curry Village, I tried to settle into the canvas tent their team had arranged for me. But I was unseasoned with this kind of camping. Over 400 tents are packed tightly into Curry Village, leaving only a thin canvas exterior between you and the hundreds of other people also communing with nature. The sounds of doors slamming shut and kids scurrying between each other’s campsites felt reminiscent of summer camp, not camping. Worse yet, I had to haul my clothing and gear from my perfectly organized van storage into my tent, somehow always forgetting the toiletries I’m used to reaching for from my bed. The tent simultaneously felt too fancy for my comfort and too rustic for my experience. Guilty as I felt to leave a tent unused, I decided it was time to revert to my way of visiting the park: illegally.

I parked the van on the far side of the Curry Village parking lot, just like I had two years ago. I covered my windows and closed the roof vent so as not to attract attention, as I’d learned to do when “camping” in the parking lot. If a ranger came, I’d just move to a pull-off further away from the village. At peace with my solo dirtbag accommodations, bizarre as they were, I curled up in the back of the van to pass out before a long day ahead.

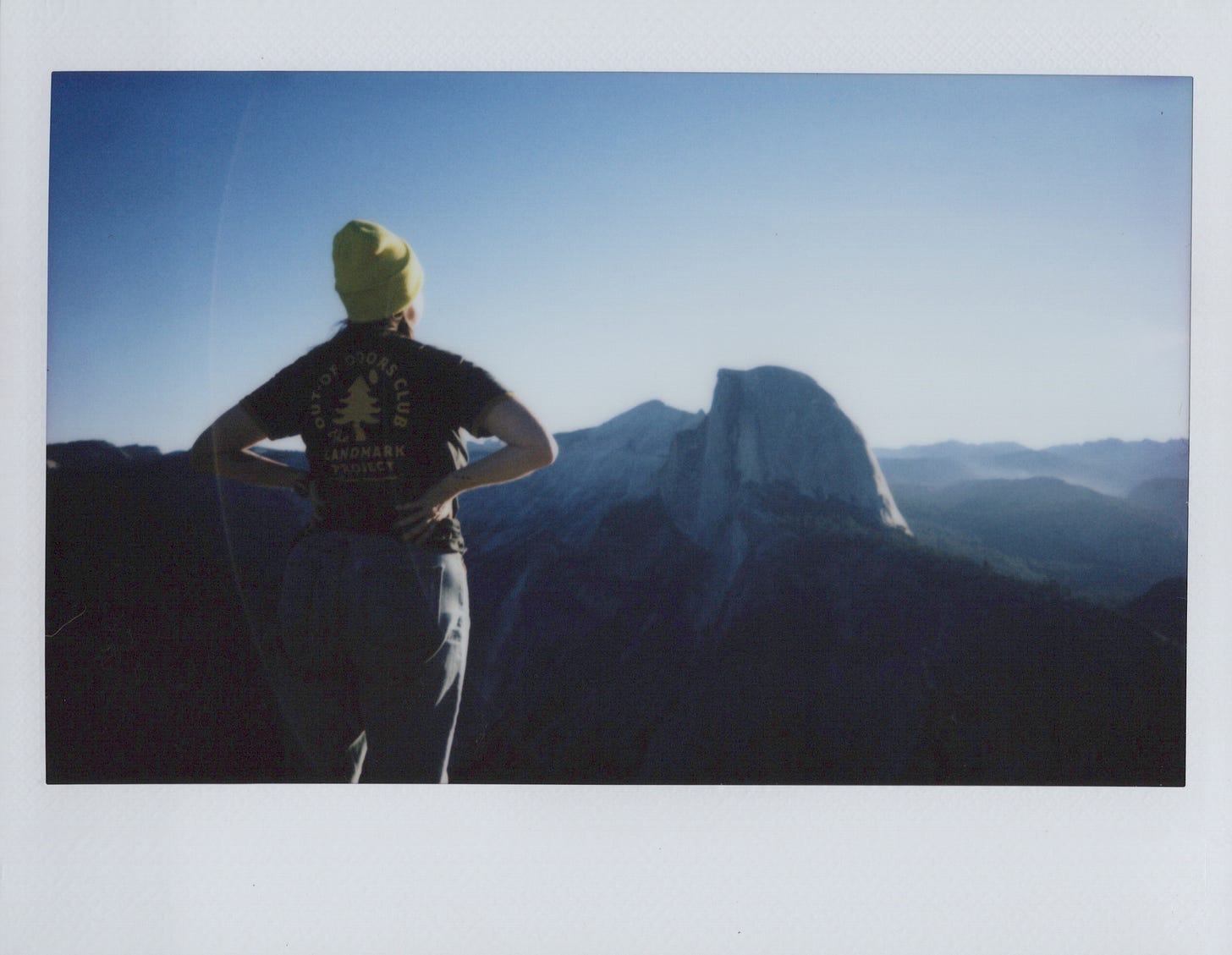

4:45 am is surprisingly bustling in Yosemite Village. Hikers in headlamps and microfleece jackets make their way in the dark to trailheads. Dots of lights scale the face of El Cap like fireflies before dawn. Cars load up and haul families to their first big site of the day. And I met the team at their campsite to roll out together to Glacier Point to watch the sunrise over Half Dome.

I was joined by Hannah, a writer and photographer from Mountain Gazette, for the hour-long commute. The dizzying traffic signs and counter-intuitive road directions were difficult enough to navigate during the day – in the pitch-black morning, running on little sleep, it was nearly impossible, even with two sets of dreary eyes. After an illegal lane change and redirect, we ascended the winding mountain roads. The hairpin curves along steep, unseeable drop-offs were what my grandpaw would have called “kiss-your-ass” turns. Hannah adjusted her camera lens against the mountain ridges, growing lighter in the distance. Rushing to meet the sun, we parked and hustled over to the viewpoint, exactly 3,200 feet directly above where we had met that morning.

Half Dome stood proudly in the foreground of the horizon line, distinct from the granite peaks around it. Slowly, almost imperceptively, the hues of the sky shifted from dusty purple to clear blue, illuminating the soft curve of the dome. As I watched, I remembered when I was a kid, and my mom dragged us out of our tents one morning to watch the sunrise from that very spot. She bundled us in emergency blankets because we’d misjudged how cold the top would be compared to the valley below. My brother and I bitched and moaned incessantly about the cold and the early morning until the sun slid out from behind the rock, and all was warm and exciting again. I don’t remember what hikes we did or what sites we saw when I visited as a child, but I remember how it felt to see Half Dome struck by dawn’s first light. It was a feeling that would inspire me to summit the Dome myself after a decades-long fixation with the accolade. Children don’t always appreciate nature as we want them to, but that lack of context makes their wonderment even more inspiring, creative, and hopeful to me.

After the sunrise faded into daytime light, we regrouped to hike Sentinel Dome. “It’s a short hike,” Matt ensured. “No pressure to join, but it’s an incredible view.” A cup of coffee in the parking lot later and I was ready to ignore the fact that I hadn’t hiked in months.

On the slow, steep hike up the granite face, I got to know my cohort of content creators more. Tuan is a fellow van-lifer and part-time forester from British Columbia living out of his pick-up truck camper. We hit our respective vapes and commiserated over the frustrations of living nomadically while trying to make money. An Asian-Canadian, he was new to the American West and even more awe-struck than I was by the vastness of California’s wilderness. To make money in the off-season, he makes funny and unexpectedly beautiful videos about trying to explain his dirtbag lifestyle to his parents. I could empathize.

Cody and Victoria are climbers from the Lake Tahoe area and are very familiar with Yosemite’s role in climbing history. “The walls are challenging but generally flat, and the granite is sort of soft on your fingers. It’s kind of the climber’s paradise.” Victoria, limping slightly from a recent climbing injury, still had more gumption to hike than I did. “We’ll probably live in the park for a few more weeks to climb after this.”

“Really?” I asked her. “Do people tend to do that?”

She smiled, “Definitely. If not in the park, then we’ll go right outside. Climbers have a history of making an unofficial home in the park for a few weeks. Some people last months, or I’ve heard, even years.” I loved the idea of climbers evading the park rangers long enough to make this mecca of granite their home. She thought I’d love the movie Valley Uprising.

At the top, we strategized what to do for the rest of the day. In true form, I could only think of one thing: how satisfying it’d be to jump into the Merced River after a hot day of hiking. “I’m thinking of heading down to some water after lunch, if anyone wants to join.” The idea caught on more than I expected, and we all made plans to meet at Housekeeping Beach in the early afternoon. We drove back into the valley to meet back after lunch.

Just as I started walking to the beach, I ran into another creator in our group, Kendra. We decided to walk the winding paths together to find the group. Hailing from Sacramento, Kendra has been making a name for herself as a National Parks travel expert on a mission to plan a thoughtful visit to each one, as opposed to my strategy of speed-running them all in two years. Though our approaches could not be more different, we had a much more important thing in common: we had both found our freedom in the National Parks after shitty relationships ended and shared a passion for women traveling solo in nature. After trying a few spots along the river, we found the rest of the team and joined them to swim near a pedestrian bridge.

The Merced River was freezing, even late into September’s long-melted waterfalls. The team took turns plunging into the frigid waters and immediately drying off in the few hours of direct sunlight when the light passed over the narrow valley. I dove head-first into the polar plunge without much thought, allowing waves of icy water to subsume me. Just as fast as I’d dove, I was back on the beach, attempting to normalize my body temperature and chatting with the Landmark team.

“In all my years of coming to Yosemite, I’ve never swam in the river,” Matt, the resident Yosemite expert, confessed.

“Really?” I asked. “It’s such a privilege to be able to swim in a natural body of water. I’m so envious of places like Boulder and Austin that have clean, in-city swimming. I guess I look for it everywhere I go.”

He agreed. As residents of southern cities, we both understood the historical context for our rivers being unswimmable: our cities were designed for industry, not recreation. But he had some hope for Greenville: “We have a fantastic, volunteer-run organization cleaning up the Reedy River. Full-time, I think that it’s only one person. But I donate and volunteer when I can, because it feels like the most direct environmental benefit I can be a part of. It’s right in my backyard.”

In the background, the rest of the team swapped disparate pieces of information about the incoming hurricane. Without much cell phone service, it was difficult and increasingly stressful to be away from home, even in a place as beautiful as Yosemite. I felt guilty for enjoying my time in the sun while my partner back home battened down the hatches for Hurricane Helene and helpless from so far away. But we were still there to do environmental work, even if it wasn’t in our own backyards just yet.

Half an hour of swimming and sunbathing later, our group was interrupted by a parade of sixth graders crossing the bridge, eyes widely set on the same swimming hole. They crashed into the water with excited screams and rambunctious joy at the expense of our quiet worrying. We gave it a few respectful minutes before calling it a day.

Heading back, I was thrilled to repurpose the canvas tent by giving the keys to Kendra for the night. By 4 pm, I was physically and socially exhausted from the day and looking forward to another cozy night in the parking lot. Still, I made use of the facilities ahead of our big day of volunteering and made use of the facilities, chaotic as they were.

The most important thing I needed was a shower. This would have been easier to accomplish without the barrage of pre-teen girls flitting endlessly between the shared showering spaces as if constantly checking each other’s progress, anxious not to fall behind or be done too early. My patience ran thin after a day of social interaction and consistently avoiding loud children. Once I finally found an open stall, I joined my fellow girlies in getting ready for the evening.

“Did Ms. Matthews say we needed to be there soon?” one of the stalls asked.

The 11-year-old girl at the vanity answered, “We need to be out of here in ten minutes,” with the confidence I’d expect of a much older teenager.

There was a gasp from three or four other girls from behind the locker room curtains. “We’ll never make it in time!” lamented one of the girls. “I’m not ready!” they cried. All five or six girls yapped loudly on top of each other, narrating their progress and communally deciding on dinner plans. Were they here on an organized field trip? I couldn’t imagine a world where a school outing would take me to a place like Yosemite National Park. Then again, I was about their age when I’d taken this place for granted the first time.

Accustomed to paid, cold showers, I finished washing my hair in rapid time and approached the vanity to finish my routine. The young woman standing at the sink could not have been older than sixth grade, yet groomed herself with multiple serums and advanced hair products. What did she know about college peptides and eye masks? At her age, I’d have been smearing Claire’s glitter eyeshadow across my lips and calling it gloss. But she continued her encouragement, “It’s okay, girls! We’ll get there on time; just focus on getting done, and we can make it to dinner!” They all squealed in agreement. I left with my hair still wet.

Curry Village was, again, run amok with youths and scant parental supervision. I wove through the parking lot scattered with truck beds full of shirtless young men (pearl clutch!), unfurling their climbing equipment from the day. I focused on getting to the visitor’s lounge for some much-needed WiFi and screen time, only to be met with dozens of kids loudly playing games while their adults waited in an unreasonably long line for pizza. Admittedly, the largest demographic of lounge users was me: an irritated adult looking for an internet fix in the middle of the most beautiful place in the world. I opened my laptop to make notes for the day and download something on Netflix; almost instantly, my screen went black, and all of my work disappeared in an instant. That was it. I was fucked for the day. Everything that was mildly annoying became utterly unbearable. I gave up and walked back to the parking lot, stopping off at the market for some overpriced Oreos and to watch a 20-year-old behind the counter get fussed at by a middle-aged tourist for not having fresh kettle corn in stock.

I just needed to sleep it off and was confident I could do so, even among the parking lot activity. It was my comfort zone, after all. At 8 pm, I completely crashed asleep in my van’s bed.

Three hours later, I was awoken by an undeniable, persistent knock. I knew what that knock meant. I could not ignore the knock and expect it to go away. I wearily grabbed my glasses and opened the sliding side door to see a young ranger standing there with a flashlight. “You can’t sleep in the lot, ma’am,” he assured me.

I sighed. “I have a tent in Curry Village. I just... I don’t want to sleep there. I’m sorry, but it’s just too many kids. They’re so loud and they’re everywhere. I have a parking pass for Curry Village right here, see?”

He examined my paper waiver for a moment and nodded. “Okay, that’s okay. Have a good night, ma’am.” And he left me alone to pass out once again.

Volunteer day had finally arrived on a brisk Friday morning. The Greenville team was still distracted by inconsistent access to weather news of their homes and Helene. Groups of volunteers, rangers, and climbing association members clamored about looking for their project teams. We gathered together with our designated park rangers, Michael and Rudy, for an explainer of the day. Despite lack of sleep or nerves outside the park, we had one collective focus for the day: to save some seeds.

Donning orange safety vests, our group hiked towards Cooks Meadow at the heart of Yosemite Valley for an explainer of the day. Both rangers had an airy excitement to their intros, clearly well-educated on conservation, albeit a little green in their presentation. “We will be collecting seeds from goldenrod, milkweed, and mint plants native to the meadows here,” Ranger Rudy explained. “Once collected, we’ll dry, process, and replant them to restore the grounds after we finish this season’s maintenance projects. Think, like, projects like upgrading the campgrounds or waste facilities. Kinda nasty to think about. But those things require machinery and some destruction in the process. So we’ll use these seeds from the meadow to restore the grounds after the season ends.”

Ranger Michael chimed in, “This is a special opportunity to be in the meadows. Take your time moving through this ecosystem; fan out, and try not to harvest more than thirty percent of what’s there. Move at a plant’s pace. The public is not allowed to be out here without a volunteer vest, so be sure to enjoy your time here.”

The meadows of Yosemite Valley are a microcosm of the park’s conservation efforts. Comprised of only 3% of the park’s area, the meadows are responsible for most of its ecological and biological diversity.2 They closed to the public in 2002 for a six-year-long restoration project focused on restoring their natural beauty and role in Yosemite’s ecosystem3 and have retained their integrity and exclusivity since. The effort included both reversing the damage of early European settlers by filling in drainage ditches and removing roadbeds and by reengineering better systems like installing culverts and removing non-native plants. Even if the visiting public is unaware of the meadows, they are likely affected by it: most of San Francisco’s water is filtered through this landscape. How to keep it, and the rest of the park, healthy and safe for generations to come is the central struggle of the Facelift event.

“If you need to frolic a bit,” Ranger Michael added, “now would be the time to do it. This might be the only time you can frolic in this meadow, ecologically speaking. If I saw a normal tourist belly-flopping into the field, we’d have to be like, ‘get outta there!’ But not today – today, you can frolic.”

We all spread out into the dry, beige field to begin our work. Half Dome stood prominently in the distance, observing our service to it like a deity. In the late summer season, the tops of the goldenrod flowers flaked off into my fingertips without much coaxing as I gathered them into a brown paper bag. Crunching slowly along the grassy mounds, I watched little white puffballs of milkweed dance off in the wind. I sighed and air passed through my lungs effortlessly. I couldn’t help it: I flopped down into the meadow with my arms spread open like a grass angel. Everything fell silent, save for the brush of grass against dried meadow flowers.

Strange to think the meadows were also the site of Yosemite’s most dramatic clash with its most adoring fans. As preservationists encouraged officials to restrict access to the park, more anti-establishment youths descended into the valley through the late 1960s.4 Violence erupted on July 4, 1970, as Vietnam War protesters clashed with federal law enforcement right in Stoneman Meadows. “Mounted rangers rode into a crowd of youths and pushed them back by force. Rock throwing, fights with rangers, and attacks on patrol cars continued throughout the evening.”5 Though many were not climbers, their shaggy-haired, rebellious reputation preceded them, as Valley Uprising explains. The delicate relationships between the federal government, the free-loading dirtbags, and the innocent public have been a tedious slough towards collaboration ever since.

I popped up from the meadow to see the team shifting south towards the shade. Kendra helped me out of my grassy divot and towards our break. Over bagged lunches, Ranger Rudy pitched Matt on a “dark redemption arch Smokey, the Bear” t-shirt idea, to which Matt nodded along earnestly before rejecting it. We finally moved into the last section of the day, following Ranger Michael as I asked him about conservation in the park.

“It’s just frustrating when people think the park needs to be saved from humans, as if humans haven’t been here, shaping the valley for thousands of years. We can’t go back to some pristine thing that never existed. We can only move forward and try to conserve this place for future generations.”

“I get that,” I added, “it’s like when people get mad at kids for being rambunctious in nature, but really, we should just be happy to see them out in the park.” I surprised myself with the argument.

“Exactly. And our park surveys show that different demographics enjoy the park differently. For instance, the picnic areas are used most often by Hispanic families who gather together for events. But then, some people complain about the noise. It’s like, what do you think Native people were doing here before if not gathering and celebrating together? ”

John Muir, one of the foundational figures of Yosemite Valley, believed in preservation – the act of protecting the park in its untouched glory, devoid of as much human activity as possible. This mentality helped stave off retrospectively insane development projects, like building a visible gondola through the valley and up to Washburn Point.6 But Muir is a figure forever at odds with changing sentiments.7 In its delicate collaboration between groups historically at odds with each other, the park practices a blend of conservation efforts – projects that actively shape and improve the park to keep Yosemite alive for generations to come. That means acknowledging that all people have a right to visit the park, and the best they can do is continually innovate to manage it. Conserve, not preserve.

The sun had reached its longest, most palpable placement in the narrow sky. I trudged to a bench along the boardwalk to chug water in the shade. I must have looked official in my vest as a small group of curious tourists gathered around my resting rock. ‘Whatcha doin’ out there?” a bystander asked.

“We’re collecting seeds to replant native species again in the spring. It’s a yearly conservation effort they do to help keep the park safe.” A collection of middle schoolers also appeared at my lecture. “So, you see, it’s important that we play our role in helping the ecosystem here thrive. They’ll use these seeds to fix other areas of the park damaged by visitors and upgrades. It’s all one big cycle.”

“Do you have monarch butterflies in the meadows?” an older man asked me.

“Oh, hah, I’m not sure, actually; I don’t work here,” I explained. “Just a big fan.” I’d become a conservation advocate without even noticing.

The team wrapped the day with one more cold plunge into the Merced River and a circle around the fire for dinner. We shared our highlights from the trip through weary yawns. I showed up over an hour late with a pizza in hand, the delay courtesy of three overworked teenagers in the Curry Village Pizza kitchen. Many of us were growing anxious to be back east, where our environmental efforts needed to continue. Each of us would leave the park with a different application of this massive conservation effort, ready to apply these lessons in our own backyards. Each of us now keenly aware of the role we have to play in keeping our ecosystems healthy, even if that means offering nature a helping hand. We all parted ways, hopeful to get started once again.

On my way out of the park the next morning, I stopped off at Mariposa Grove to tour the giant sequoias. One can hike their way up to see the grove, but most tourists, myself included, take the shuttle established to accommodate an additional parking lot. Young families with strollers adjusted their spacing to allow room for a tour bus full of elderly Korean tourists to join the crowded commute. As we drove slowly up the steep hillside, the driver pointed out important sites on either side, adding: “See all these burned trees? That was from an arsonist two years ago.8 Even though the trees are burned, many of them are still alive. They have evolved to withstand a certain amount of human interference.”

A blend of conservation tactics helped contain the fire within a month.9 This included the Indigenous practice of proactive prescribed burns,10 which many white preservationists of the mid-century saw as harmful interference in the natural world. While the clash of different people has caused violence in the park, it’s also forced a degree of diverse cooperation, as each entity accepts, at this point, that they need each other and each unique expertise to survive.

Some problems in Yosemite National Park have nothing to do with the number of people visiting at all but rather with how those people are taken care of. Earlier this year, reports began to surface that Yosemite’s facilities contractor had failed to meet basic health and safety standards.11 Basic things like staffing, cleaning, and maintaining historical facilities have gotten significantly, demonstrably worse since 201612 in the name of government cost-cutting. The news didn’t surprise me: this is the same corporation that my own alma mater had to kick off campus after mass student protests for poor treatment of staff and failed safety standards.13 So while the in-fighting between rangers, climbers, and visitors continues to nitpick and define exactly how we should enjoy the park, maybe there is unity against a common enemy: those who treat the public nature like a business14 instead of increasing15 funding to make managing all of these competing interests easier.

I hopped off the shuttle and made a beeline for the trailhead ahead of the crowds, only to be met with more along the path. Two teenage girls in long skirts and big headphones stood off to the side, taking moody pictures in front of a fallen conifer. A Boomer man took a heavy rest against the path’s wooden railing by loudly watching the Michigan game from his phone. President Theodore Roosevelt once proclaimed, "There can be nothing in the world more beautiful than the Yosemite, the groves of the giant sequoias...our people should see to it that they are preserved for their children and their children's children forever, with their majestic beauty all unmarred." As enraptured as he had been on his trip to Yosemite Valley with John Muir, Teddy still focused on one main element: people need to see this place. We must keep this place healthy for generations of people to experience.

Deep along the trail, silence finally fell. The towering grove around me seemed to absorb every sound I made and amplify every thought I had. Bright green saplings and sprigs of purple wildflowers overtook patches of charred stumps. Standing like an ant among the red giants, it was almost an insult to consider that my tiny act of spreading a few seeds one day would even be a blip along the three-thousand-year evolution of this park. They have and will outlive us all.

A girl approached and broke the overwhelming silence with an ask. “Do you want me to take your picture here?” I thanked her for offering and stood deliberately next to a patch of goldenrod at the foot of a giant sequoia. “What kinds of plants are those?” she asked.

“They’re goldenrod,” I responded. “They’re native plants that help keep the ecosystem healthy.” I smiled at the camera. It’s never too late.

https://www.intermountainhistories.org/items/show/339

https://www.nps.gov/yose/learn/nature/meadows.htm

https://www.nps.gov/yose/learn/nature/ecorestoration.htm

https://foresthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Childers_Stoneman.pdf

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/runte2/chap13.htm

https://yosemite.org/alternate-histories-yosemite/

https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2021-2-march-april/feature/john-muir-native-america

https://www.mercurynews.com/2022/07/11/yosemite-blaze-was-a-human-start-fire-park-superintendent-says/

https://fireecology.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s42408-023-00202-6

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/fire/indigenous-fire-practices-shape-our-land.htm

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-09-20/in-yosemite-national-park-aramark-s-problems-keep-piling-up

https://www.sfchronicle.com/california/article/yosemite-aramark-19446674.php

https://www.theeagleonline.com/article/2019/09/satire-aramark-in-memoriam

https://lasvegassun.com/news/2024/sep/11/government-shouldnt-be-run-like-a-business-and-cer/

https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1207/president-proposes-$3-57-billion-national-park-service-budget-in-fy-2025.htm