The Presidents and the Parks

What does National Parks Week mean to a president on a rampage against them?

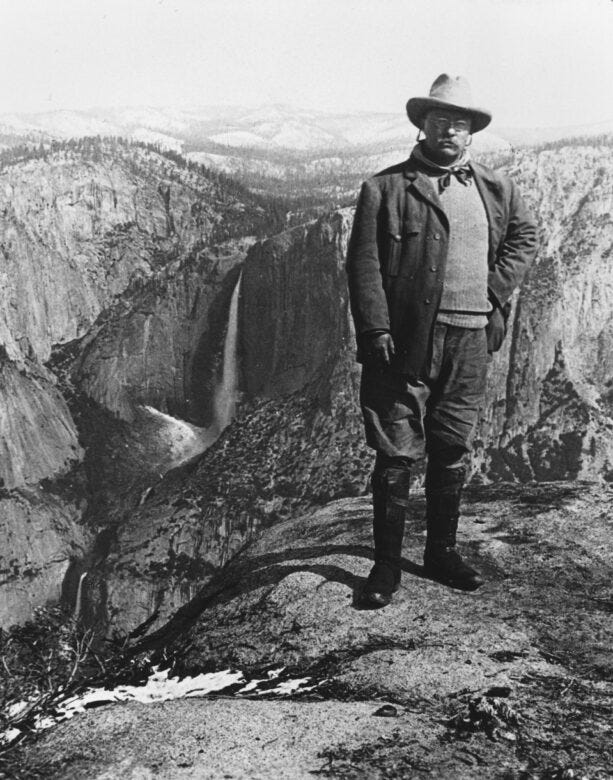

"There can be nothing in the world more beautiful than the Yosemite, the groves of the giant sequoias and redwoods, the Canyon of the Colorado, the Canyon of the Yellowstone, the Three Tetons; and our people should see to it that they are preserved for their children and their children's children forever, with their majestic beauty all unmarred." - Teddy Roosevelt, Outdoor Pastimes of an American Hunter, 1905.

It’s National Parks Week, when Americans are encouraged to explore our country’s “best idea” ahead of the increasingly busy summer season. In his proclamation this week, President Donald Trump declared it a time “we renew our pledge to cherish and protect our magnificent symbols of American greatness.” Normally, it’s a celebratory commencement of events, volunteering, and free access to our most beloved public lands.

But a deep discomfort looms over trip planning this year. Visitors are struggling with the decision to cancel trips, worried that attendance will only contribute to the chaos. To make a bad situation worse, this week, DOGE took control of the Department of the Interior, which oversees the National Parks System and Bureau of Land Management. Based on the administration's actions so far, from opening public forests to private logging to shrinking national monuments to allow private mining, the “pledge to cherish” these parks feels like a hollow offer. We have entered a new round of struggles in a long-standing tension between public access and private “streamlining,” between natural glory and human supremacy, between democracy and efficiency.

Even before the federal government first set aside land for preservation and public use in 1864, it was already clear what commercial interests could quickly do to a natural landmark. In the industrialized Northeast, natural tourist sites were overrun by private businesses charging admission or even access to view. Josiah Dwight Whitney, director of the California Geological Survey, warned in 1868 that Yosemite Valley faced the sad prospect of turning into a great swindle "like Niagara Falls, a gigantic institution for fleecing the public. The screws will be put on," he predicted, "just as fast as the public can be educated into bearing the pressure.”

It’s not the presence of humans that threatens nature (humans have always been a part of the land, regardless of the manifest mythology of an uninhabited West) — it’s the threat of unchecked human dominance over nature. To protect Yosemite from the fate of rapid commercialization, President Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant into legislation, setting a precedent for the creation of Yellowstone National Park, the nation's first, within the decade. It also, however, laid the groundwork for a never-ending debate over how to balance preservation and increased tourism as love for the park grew.

Since then, National Parks have served as something of a snapshot of the current American political culture. They show us what was important to a president, given the state of the nation, both professionally and personally. They show us what we’re desperate to hold on to.

No president’s love of public lands compares to Teddy Roosevelt, whose 1903 hike into Yosemite would change the landscape of America. For three nights, he accompanied conservationist John Muir on a trip to camp among the giant sequoias and under the open sky of Yosemite Valley. He wrote of his time camping in Yosemite that "It was like lying in a great solemn cathedral, far vaster and more beautiful than any built by the hand of man."

The trip impacted him so profoundly that he would double the number of National Parks, sign the landmark Antiquities Act to create 18 national monuments (including the Grand Canyon), and set aside 51 federal bird sanctuaries, four national game refuges, and more than 100 million acres' worth of national forests. Going to a National Park changes people, even the world’s most powerful men, who can’t help but shrink in the face of untamed wilderness.

His distant cousin, Franklin D Roosevelt, would follow in this tradition by greatly expanding national support to public lands through the New Deal. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) federally employed 3 million men with manual labor jobs related to the conservation and development of natural resources in rural lands. The program was wildly productive, creating state parks, fighting fires, building roads and infrastructure, and paving the way for the public to access nature for the first time. The CCC remained popular until the draft reduced the need for work relief, and Congress voted to close the program in 1942.

"Of all the questions which can come before this nation, short of the actual preservation of its existence in a great war, there is none which compares in importance with the great central task of leaving this land even a better land for our descendants than it is for us." - Teddy Roosevelt’s speech on “New Nationalism,” 1910

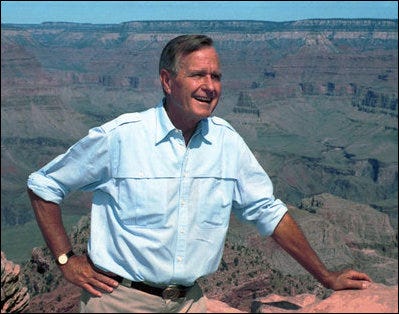

But it’s not just the Roosevelts — presidents visiting national parks is part of a long tradition. Old-school presidents used them to explore the outdoors during their terms: Coolidge went fishing at Yellowstone, Hoover enjoyed the hills of what would become Shenandoah, and Eisenhower was so moved by the Pennsylvania mountains that he made a retirement home of Gettysburg. Mid-century presidents engaged more directly, as Kennedy took a personal interest in protecting national seashores. Johnson, through his wife Lady Bird, supported beautification efforts on public lands across the country, and Ford was a summer ranger at Yellowstone before visiting it later in his official capacity. The Bushes loved National Parks: Senior toured Yellowstone, Grand Teton, the Everglades, the Grand Canyon, and Mount Rushmore during his presidency, while his son visited Sequoia, Mount Rushmore, Shenandoah, Zion, and Grand Teton during his tenure. The Clinton family and the Obama family visited Yellowstone, Grand Teton, the Grand Canyon, and Acadia National Parks during their time in office. Hell, Harding died trying to visit Yosemite.

These visits to a National Park can be transformative experiences. Standing at the edge of the unfathomably large Grand Canyon will challenge you. Staring up at the giant redwoods of Sequoia will humble you. Descending down into the Wind Cave will quiet you. Even the most powerful men in history can’t help but praise in awe the open American wilderness.

So, as the Trump Administration continues its rampage against the National Parks, from dismantling the workforce to opening public lands to logging, I couldn’t help but wonder: has Donald Trump ever been to a National Park?

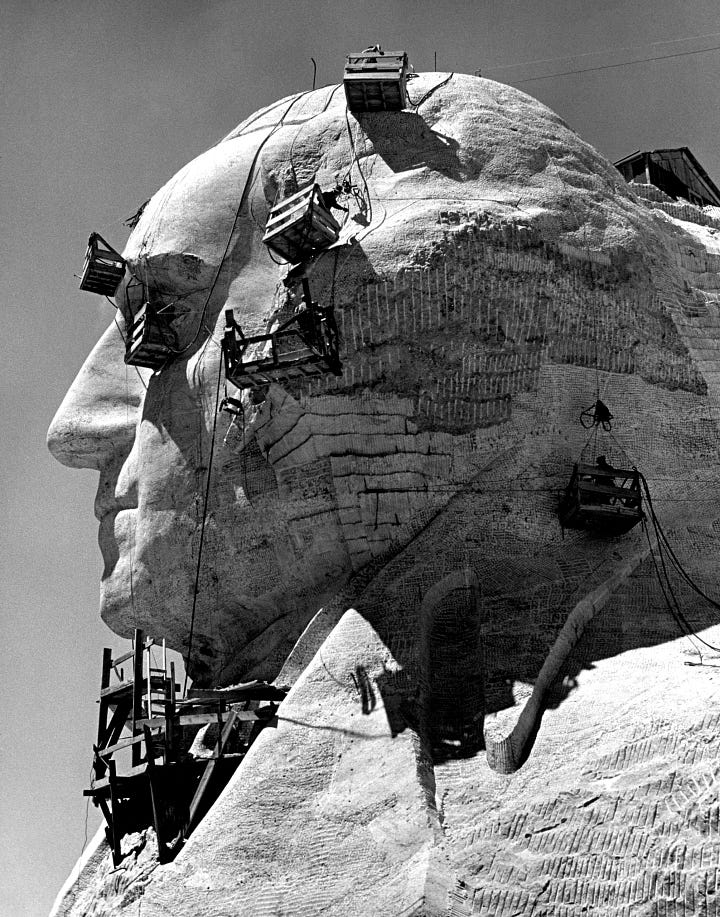

I could only find evidence of one public visit Trump made to a National Park, back in 2020. At the height of the COVID pandemic, amid a summer of racial justice protests, four months from an election, Trump made an Independence Day speech at Mount Rushmore. Unlike presidents past, it was not a speech about the importance of conservation or the majesty of the natural world, but rather on defending “heritage” and criticizing what he described as a “left-wing cultural revolution designed to overthrow the American Revolution." Though the themes were not necessarily new for him, the speech was the most overtly ideological, theatrical, and polarizing expression of them, only amplified by the dramatic backdrop.

Honestly, Mount Rushmore is the perfect stage to antagonize your enemies. The tourist trap was designed and sculpted by Gutzon Borglum beginning in 1927, fresh off his ouster from the Stone Mountain project due to creative differences with its funders and commissioners, the Ku Klux Klan. The Secretary of the South Dakota State Historical Society, Doane Robinson, admired his unfinished shrine to the Confederacy so much that he hired Borglum to create a representation “not only the wild grandeur of its local geography but also the triumph of Western civilization over that geography” on illegally seized Sioux land. The National Park took the monument under its jurisdiction in 1933 to encourage its completion, as Borglum’s personal ambitions inflated the cost and number of heads. Borglum died before Lincoln had a full chin, and the project closed in 1941 due to lack of funding.

When I visited just over a year after Trump’s speech, eager to see the majesty of American iconography, I was admittedly disappointed. Their faces, less prominent than I’d been sold, were made smaller by their distance from the viewing platform. The pile of rubble at the bust of an unfinished George Washington left me feeling both sad and embarrassed that this is how we chose to protect the indescribable natural beauty of the Black Hills. At a time when America was spiraling rapidly into the Great Depression, the government chose to carve a shrine to itself and abandoned it short of completion to fund the war instead.

After I’d stared at it long enough, I walked away from the washed-out monument, through the concrete pathway lined with state flags, past the welcome center, onward into the woods. The hazy sun of late afternoon faded to a deeper gold as I walked, until the space between the white spruce trees thickened and obscured the path ahead and the roadways behind. And there were no speeches, only sounds.

Standing at the base of the imposing, craggy peaks deep in the wooded calm of South Dakota, I still felt a sweeping connection to all of it. To the ponderosa pines surrounding me on every side. To the elk and the bighorn sheep and ospreys in waiting. To the triumphs and sins of my countrymen, shared lineage or not. All of it.

Among the myriad reasons I could give for visiting a National Park, I found this to be most true: seeing the beauty of the vast and wild country reminds me that America is more than its flawed people – it’s a sprawling ecosystem of overlapping biomes, ideas, organisms, and histories. It is a reminder that my time here in this place is merely a drop in the bucket for a redwood, let alone a granite mountainside. It is a call to defend it more than ever, and an acceptance that it will continue without me either way. Maybe that’s why some presidents can’t handle visiting a park: Their egos cannot bear the weight of cosmic insignificance.

"We have become great because of the lavish use of our resources. But the time has come to inquire seriously what will happen when our forests are gone, when the coal, the iron, the oil, and the gas are exhausted, when the soils have still further impoverished and washed into the streams, polluting the rivers, denuding the fields and obstructing navigation." - Teddy Roosevelt in his speech at the Conference of Governors, 1908

Love it! 🙌🏾

Emily so well-written and such good research to help remind me of the great resource we have in our natural parks, how they’ve been cherished and cared for by so many and the importance to help preserve …and visit them.